July 11th, 2022: The National Archives (TNA) withdrew the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO – FCDO’s predecessor) 141 collection from public use for a health and safety assessment.

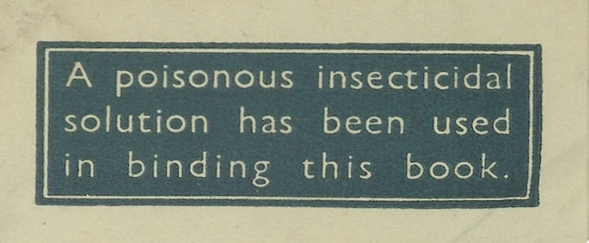

In a press release it stated the action was “due to evidence of historical preservation treatment of these files indicating insecticide use.” Small labels were found inside various documents (see above), and these documents, produced and treated in the UK and sent to its colonies to be used by administrators, were manufactured as such to discourage “ravaging” by “enemies of books”. Other indications of insecticide treatment include white powder and water mark-like blotches.

Although the collection was reinstated three months later on October 11th, the public kept a close eye on TNA during this 92 day limbo.

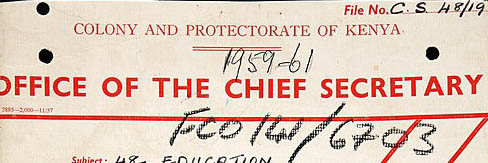

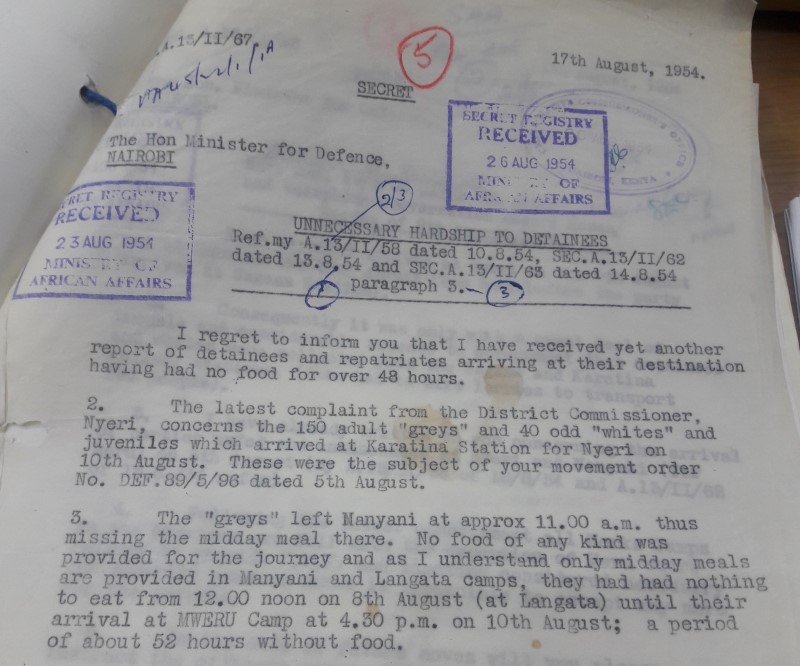

FCO 141, also known as the ‘Migrated Archives’, is the abbreviated name describing a collection of some 20,000 administrative files exported from former British colonies to England following the mid-20th century wave of national independence movements.

If you’re familiar with the collection, you’ll know they’ve been at TNA for a decade. So why restrict them now? Its initial press release stipulated that the discovery of these labels came amidst digitisation efforts, though it begs the question of another ‘why’, why weren’t these labels discovered earlier despite the collection’s wide use? There is a warranted lack of trust surrounding FCO 141.

The collection’s history has been highly scrutinised for its lack of transparency. Its existence was unknown until recently. After decades of secrecy, it was acknowledged publicly by the then FCO in 2011 amidst the landmark Mau Mau legal proceeding in London – its documents proving British colonial brutality towards Kenyans. Nearly £20 million was paid in compensation to more than 5,000 Kenyans who were found to have been tortured and abused by the former colonial administration. TNA received the documents during the trial, and subsequently made them public on April 18th, 2012.

Two days after TNA’s statement of withdrawal of FCO 141, SCOLMA (the UK Libraries and Archives Group on Africa) wrote an open letter to the institution asking for frequent updates throughout the process. TNA responded to the enquiry a few weeks later, and with two additional public updates throughout August, apologising for its delay, but with minimal information on the procedure.

Two weeks after the collection’s withdrawal, Dr. Mandy Banton, author of Administering the Empire, 1801-1968: A Guide to the Records of the Colonial Office in the National Archives of the UK and Senior Research Fellow at the School of Advanced Studies, expressed dissatisfaction with TNA’s handling of the matter. Crucially, she stated how summer months are prime time for academics to travel overseas for research, and that TNA “treated researchers wishing to use the documentation with indifference, if not contempt.”

June 22nd, 2023: Nearly one year on, TNA hosted a public event for scholars, librarians, archivists, and other academics to exchange knowledge on the historic use of insecticide treated documents in response to FCO 141’s withdrawal.

Representatives from various institutions spoke about their encounters with harmful substances in their collections, and how they dealt with the issue. The cases included King’s College’s FCDO collection (100,000+ items), Durham University’s Sudan Archive (256m of material), and Harvard’s acquisition of twentieth-century books (4000+) in Persian and Urdu.

The outcomes of the above entities have been relatively positive. Each, including TNA, resourced health and safety consultancies to aid the physical assessment of materials. Harvard, for example, published an article outlining how the discovery of harmful powder in its collection led to new channels of collaboration within the university between researchers, administrators, librarians, and the community. King’s and Durham expressed the community’s welcome cooperation with new user guidelines.

There are largely no physical health risks to handling documents treated with insecticides. These institutions have introduced policy requiring users examining the collections to use disposable nitrile gloves and have increased sanitary measures.

Though its full report is yet to be published, TNA compiled an FAQ list about FCO 141’s withdrawal and its preliminary new steps for handling the collection.

The Cambridge Centre of African Studies Library hasn’t identified any traces of insecticide treated materials in its collection and, with the helpful understanding of other institutions’ experiences, is equipped for action should signs of these chemicals be discovered.